Contrast First Century Dress for Women in Israel and Babylon

Clothes in the ancient world

What did they wear? Bible Study Resource

Over many centuries the Jews, and the early Christians as well, borrowed fashion from all the peoples around them. There were many influences, because they had been

- exiles in Egypt and Babylonia

- ruled by Greeks and Romans

- lived in a land which was a natural crossroads between major cultures of the ancient world

- exposed to the style of dress of the Syrians, the Canaanites and Phoenicians, the Assyrians and Babylonians, the Greeks and the Romans.

What a mix!

Materials and textiles

What did they have to work with?

In biblical times the basic textiles were wool and linen. Both could be spun rough or fine.

First, make your linen

Twisted hanks of flax fibre, late Middle Kingdom, about 1850-1750 BC

You could not, of course, go to a shop and buy cloth. You had to make your own.

Linen was favored, but making linen out of flax is quite a process. First the outer bark of the stems is removed (after it has rotted) and the fibres separated. Egyptian tablets show the flax being pressed into tubs of water, and Josiah 2:6 refers to the fibres spread out in the sun to dry.

At right are some twisted hanks of flax fibre, probably late Middle Kingdom, about 1850-1750 BC. Not much to look at, but fibre like this made linen that was sought all over the ancient world.

The long fibres were spun into thread and wound onto a spindle held in the hand. The spindle was spun round in the fingers to tighten and strengthen the thread and, to keep this even, a heavy weight known as a 'whorl' was attached to one end.

The whorls were made of clay or stone, and the large number of them found in nearly all excavations is evidence of the universal practice of the craft.

It was carried on by women (as described in Proverbs 31:19) rather than by tradesmen, whereas weaving was a trade.

Mesopotamian whorl

Weaving cloth

The threads were woven into cloth on a loom made from a long beam supported by posts or in some other way.

- The warp threads were hung from this beam, weighted down by stones or other loom weights to keep them steady.

- The weaver threw his shuttle, carrying the long weft thread, backwards and forwards between the warp to make the cloth.

The biblical loom was upright, not horizontal, and the weaving was done from the top down.

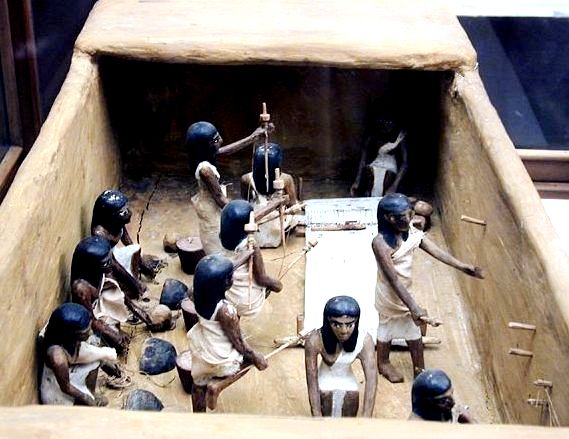

Model of a weaver's workshop with eleven workers, Cairo Museum

Illustration on a Greek vase, showing women working at a loom

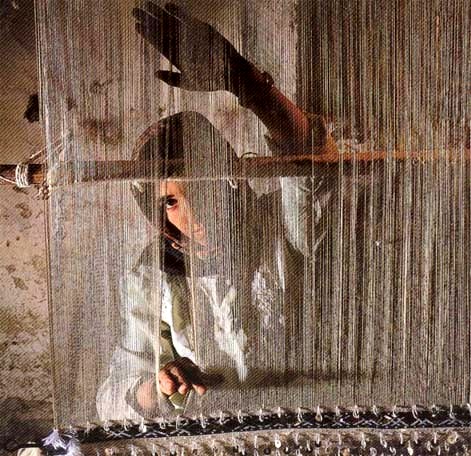

A young Middle Eastern girl sits at a loom, weaving.

Little has changed since ancient times.

When the piece of cloth was finished, the ends of the threads were knotted into fringes to prevent unravelling.

After all his tedious work, the weaver was naturally reluctant to see the cloth cut. Instead of making fitted garments, the rectangular piece of cloth would usually be draped around the body, fringes and all.

The Egyptians excelled in making fine linen, often dyeing the threads to weave coloured or patterned cloth, or embroidering the finished goods.

The Hebrews must have learned some of these skills because later on they were able to build the tabernacle with 'blue and purple and scarlet and fine twined linen, wrought with needlework' (Exodus 26:1).

In early days, the yarn was dyed in cold vats, like those of the installation at Debir (below), which dates from the 8th-6th centuries BC. In the post-Exilic period, hot vats were used for dyeing woven cloth, as was customary outside Palestine.

Vats for dying cloth, found at ancient Debir

Different types of garments

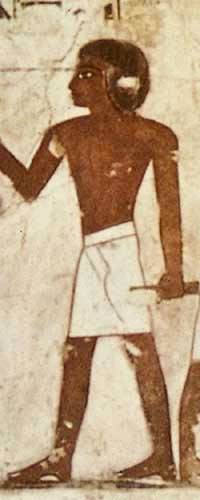

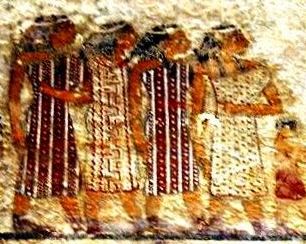

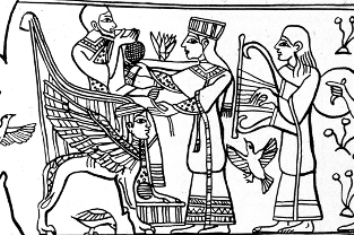

Egyptian wall painting of a young man dressed in the kiltlike loincloth called the ezor. Many Egyptian paintings show such a garment wrapped around the loins and tied with a belt or girdle

The earliest undergarment was probably the kiltlike loincloth worn next to the skin, called ezor (II Kings 1:8; Matthew 3:4). Many Egyptian paintings show such a garment wrapped around the loins and tied with a belt or girdle (hagorah), and Matthew describes John the Baptist wearing clothing like this.

For religious functions, a shirt or apron was tied around the body (I Samuel 2:18; II Samuel 6:14).

In general, the most common garment was the tunic, the ketonet, chiton, or tunica (John 19:23).

This tunic or outer garment was made by simply folding a rectangle of cloth in half and sewing up the sides, leaving openings for the head and arms. This could be worn open or closed, with or without sleeves, depending on the people or place.

The most usual Hebrew term for a top garment, possibly worn over the tunic, is the me'il, although in many cases English versions wrongly translate the term 'coat' (see Joseph's coat). Apparently it was also worn by people of high rank.

Such a costume is pictured in a borderstone of a Babylonian king (circa 1100 BC) although this one was collarless and had short sleeves ending above the elbows. Later on, evidence from the New Testament (Mark 6:9; Luke 3:11) suggests that at times people wore two coats.

The Cloak/Simlah

Tile from Medinet Habu showing a garment that seems to be wound several times around the body

In Old Testament times, most people – men and women – wore a shawl or cloak made of wool or linen draped fairly closely around the body over the tunic.

Jewish law (Deuteronomy. 22:5) makes it clear that women's clothing differed from men's.

The saddin may have been similar to the outer cloak (simlah) that was worn, for instance, by King Jehu and his attendants bringing offerings to King Shalmaneser, shown in the black obelisk of Shalmaneser.

See this image at Clothing: the evidence.

What did they wear on their heads?

Drawing of one of the tiles from Medinet Habu

The Bible tells how fine linen was wrapped around the head of the High Priest as a turban or mitre — the saniph or kidaris (Exodus 28:39).

Ordinary people wore a kerchief over the head, held tight by a cord reminiscent of the Arab headdress commonly worn today, the 'aggal.

When bareheaded, men wore a fillet to keep their long hair in place (see right, drawing of one of the tiles from Medinet Habu).

A skull cap or turban was also typical. The peasant or soldier simply wound a simple strip of cloth around the head, leaving one fringed end to hang over the right ear.

Did they wear shoes?

In ancient times men generally went barefoot indoors but outside they protected their feet with a sandal usually made of a simple sole of untanned leather, tied on with straps or latchets (Genesis 14:23; Mark 1:7).

A sandal was the cheapest thing one could imagine (Amos 2:6) — only the shoe-strap was worth less (Genesis 14:23).

Egyptian Beni Hassan painting shows men wearing thonged sandals

The Egyptian Beni Hassan painting shows women wearing soft low boots

The Egyptian Beni Hassan paintings above show men wearing thonged sandals, while the women have soft low boots of a kind still found in western Asia a few decades ago.

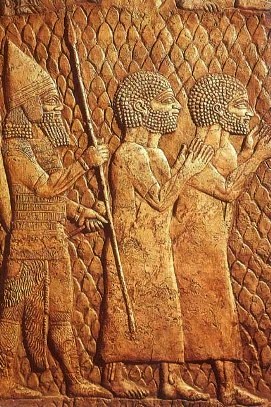

In the black obelisk of Shalmaneser shown below, tribute bearers bringing costly gifts to the Assyrian ruler appear to be shoeless or wearing light shoes. Shoes had to be removed in certain circumstances, for example in the presence of a king or ruler.

Obelisk of Shalmaneser with tribute bearers bringing gifts for the king.

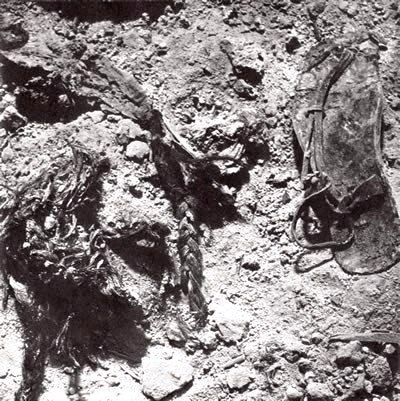

In later times a much greater elegance was achieved. A good example of second century AD footwear in Israel is the child's sandal found, with its straps still intact, in a cave of Nahal Hever, last hideout of Bar-Kochba's partisans. The other sandals were worn by adults.

Above: The sandals, with human hair,

at the excavation site at Nahal Hever

Simple strap sandals found in a cave of Nahal Hever

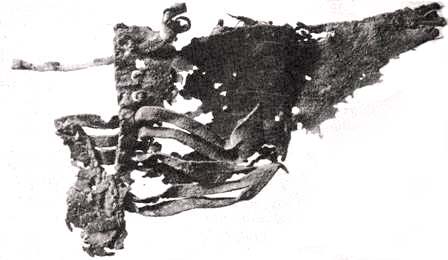

In the same cave, pieces of leather which had once formed part of a garment or bag (see below) were also found, and nearby were two samples of sewn leather which had once belonged to an outer coat.

Remnants of a leather woven bag found in the caves at Masada; it must have belonged to the people who took refuge in a cliff-face cave immediately before

the Roman legions broke through

Decoration: tassels and fringes

The tallit

Jewish people were required by their law (Numbers 15:37-41; Deut. 22:12) to put tassels (tzitzit or fringes) on the corners of their garments with a blue cord intertwined in them. This tradition is still followed by observant Jews during services, in the tasselled tzitzit knotted on the four corners of the tallit, a big fringed, four-cornered prayer shawl.

The large tallit, usually made of wool, was worn only during morning prayer and in the afternoon and for all services on the Day of Atonement.

However, a special undergarment, the "arba kanfot" (four corners) or "tallit Utan" (small tallit), was worn perpetually during waking hours under the outer garment.

The blue dye for tzitzit was obtained from the Mediterranean sea snail (murex) from which the ancients (mainly the Phoenicians) obtained blue and purple dyes. Because the use of shellfish gave rise to certain difficulties, the Talmud (Menahot 38a) later taught that all fringes might be white.

Every male garment originally had tzitzits and wearing them differentiated a zealous Jew from his neighbours. Later on, however, they were worn only on intimate garments or in the synagogue.

Clothes in the late Bronze and early Iron Ages(1300-930 BC)

The Canaanite ivory carvings of Megiddo (12th century BC) show the men wearing long sleeved robes over a coloured tunic (ketonet), embroidered in geometric designs. Over their robes the simlah is wrapped closely around the body, leaving the right shoulder and arm free. On their heads, they have close-fitting caps.

Part of an ivory carving found in the ruins of ancient Megiddo

The women are also dressed in long robes (simlah), trimmed at the neck.

- Some of the ivories show women in sleeveless dresses, some with loose sleeves, showing the long sleeves of the undertunic (ketonet).

- Some are worn open in the front, decorated with embroidery all around the edges, and with long tassels hanging down in front.

- One woman (see above) wears a wide, flat-topped headdress like a crown, over a kerchief.

- In contrast, the harpist is bare-headed, with her hair spread over her shoulders. She may be a "kedeshah" or temple-priestess.

Shalmaneser ivory

An Assyrian law stipulated that a respectable married woman must cover her head, while an unmarried girl must go bareheaded.

The carvings above and at right present a court and/or religious scene, so it may not be a good indication of ordinary Israelite costume of the period. It does show, however, that Iron Age garments were no longer fastened by means of pins, but made use of fibulae or buckles.

Late Iron Age (930-600 BC)

The black obelisk of Shamaneser III (see Clothes: the evidence) shows the Assyrian king receiving tribute from Jehu, king of Israel.

- Some of the Assyrians wear fillets on their hair, flat sandals and long, short-sleeved robes with fringes at the bottom, tied with a tasselled sash.

- Others are wearing a long skirt with fringed shawls wrapped around the shoulders and waist.

- The Assyrian king wears a fez-like cap on his head.

- The Israelites wear a long skirt or tunic — very little different from what was worn at the beginning of the Israelite era.

- Over it they wear an open short-sleeved mantle fastened on the shoulders, with fringes and tassels along the edges.

- Some of them wear fillets on their heads and others, including King Jehu, have a soft pointed hat, rather like the Phrygian cap.

- All of them are wearing shoes which cover the foot and turn up at the toes.

Assyrian sculpture of the capture of Lachish

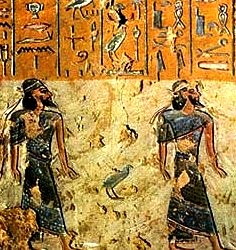

In the Assyrian sculpture of the capture of Lachish (right), captured Jewish men are dressed in a moderately tight garment fitting closely at the neck (Job 30:18) and reaching almost to the ankles. They wear nothing on their heads – these are a conquered people, at the mercy of their enemies.

Women are shown with a mantle like a long veil wrapped around the body and covering the forehead.

Clothes in Roman and New Testament times

Fashions changed little after Hellenistic times, but they acquired a Roman flavour.

The most interesting feature about Graeco-Roman clothing of the first century AD was the manner in which a long piece of cloth, the "chlamys" as the Greeks called it, or the "pallium" in Latin, was draped over the tunic in a variety of ways.

A special variety of the pallium was the "toga". The typical flowing garments of Roman citizens, with loose togas and stoles worn over them in various ways as a type of cloak, are shown on a Roman relief of 13 BC, portraying a religious procession (Ara Pacis).

Part of the Ara Pacis, showing the Imperial family

Apparently the emperor Augustus favored the austere toga as the quintessential Roman way of dressing, which is why all members of the Augustan family are shown wearing togas – even, on other parts of this sculpture, small children.

But the ordinary Romans themselves did not like wearing the toga, because it was difficult to put on and inclined to fall off unless one kept one's left arm bent upwards.

The wealthy and ruling classes in Palestine no doubt dressed like the patricians of Rome but the clothing of ordinary people — like Jesus and his disciples — was much simpler.

Apparently there were six garments :

- a linen shirt, haluk, worn underneath the tunic

- the tunic itself which might be "woven without seam" (John 19:23)

- a linen girdle wrapped around the waist (Matthew 3:4);

- leather sandals for the feet and

- an upper garment (Mark 9:3) probably made of white wool, with tassels at the corners.

In those days, Jewish teachers covered their heads, so Jesus may have worn a white linen "napkin" sudarium like a turban. The sudarium was a kind of head kerchief, and is mentioned as a covering for the heads of the dead (John 11:44; 20:7).

Draped upper tunic with loose trousers: comfort with style! 1st or 2nd century AD, from the Valley of the Tombs, Palmyra

What does the Bible say about clothes?

- Mixed materials in one piece of clothing forbidden, Deut. 22:11.

- Men forbidden to wear women's clothes, women forbidden to wear men's clothes, Deut. 22:5.

- Rules with respect to women's clothes, 1 Tim. 2:9,10; 1 Pet. 3:3.

- Cloaks not to be held over night as a pledge for debt, Ex. 22:26.

- Ceremonial purification of, Lev. 11:32; 13:47-59; Num. 31:20.

-

Various articles of clothing: Mantle, Ezra 9:3; 1 Kin. 19:13; 1 Chr. 15:27; Job 1:20; many colored, 2 Sam. 13:18; purple, John 19:2,5. Robe, Ex. 28:4; 1 Sam. 18:4. Shawls, Isa. 3:22,

Various articles of clothing: Mantle, Ezra 9:3; 1 Kin. 19:13; 1 Chr. 15:27; Job 1:20; many colored, 2 Sam. 13:18; purple, John 19:2,5. Robe, Ex. 28:4; 1 Sam. 18:4. Shawls, Isa. 3:22, - Embroidered coat, Ex. 28:4,40; 1 Sam. 2:19; Dan. 3:21.

- Sleeveless shirt, Matt. 5:40; Luke 6:29; John 19:23; Acts 9:39.

- Cloak, 2 Tim. 4:13; John 19:2,5.

- Skirts, Ezek. 5:3.

- Mufflers, Isa. 3:19. Sashes, Isa. 3:20.

- Changes of raiment, the folly of excess, Job 27:16.

- Uniform vestments kept in store for worshipers of Baal, 2 Kings 10:22,23; Zeph. 1:8;

- for wedding feasts, Matt. 22:11.

- Presents made of changes of clothes, Gen. 45:22; 1 Sam. 18:4; 2 Kin. 5:5; Esth. 6:8; Dan. 5:7.

Source: http://womeninthebible.net/bible-archaeology/clothes_ancient_bible/

0 Response to "Contrast First Century Dress for Women in Israel and Babylon"

Post a Comment